DfT Cycling (and Walking) Delivery Plan

The Government released its 10-year Delivery Plan [1] for consultation on 16 October 2014 (consultation closed on 13 November 2014).

Pre-publicity implied that the plan would be a Cycling and Walking Delivery Plan, but the title of the published draft was Cycling Delivery Plan, and out of 16 pages, there were only two paragraphs [on page 5] with any specific reference to walking - otherwise the "walking" element was almost entirely restricted to adding on "and walking" after some instances of the word "cycling".

The response from Pedestrian Safety can be downloaded from here and the text and charts from it are appended below.

The Government published its response to the consultation [2] in March 2015.

DfT Cycling (and Walking) Delivery Plan - Response from Pedestrian Safety

In outline, the vision is good:

That walking and cycling become the natural choices for shorter journeys - or as part of a longer journey- regardless of age, gender, fitness level or income

However, most of the features of a good delivery plan are missing. The following comments are made regarding walking. Following the summary are some detailed comments.

Summary points

The following comments and criticisms are made regarding walking. Some detailed comments follow this summary.

- The Plan does not comply with recommendations on good policy making.

- There is very little background evidence. Evidence that should be included (or referred to) includes pedestrian road casualty data, numbers of walking trips taken, and health effects of inactivity (e.g. obesity data), with international comparisons in each case.

- The DfT should stop judging road safety purely by total road casualties

- There is no assessment of the gap between the vision and the current facilities for pedestrians.

- There is no acknowledgement that the UK is behind other countries in provision for pedestrians, and needs to catch up.

- There is no acceptance that past decisions by politicians and officials are mainly responsible for the current obesity crisis.

- There is no mention of the moral obligation to protect children and other vulnerable pedestrians from the danger created by motor vehicles.

- There is no summary of the potential benefits of achieving the vision, in order to justify the investment of time, energy and funding.

- There is no review of previous DfT documents and actions, and the lessons learned.

- There is no consideration of why the vision (which is not new) is not already a reality.

- There is no consideration of a Vision Zero / Safe System approach.

- There is no review of the current Road Safety Strategic Framework, which seems to be having no effect on pedestrian casualties.

- There is no review of specific measures that have been recommended in numerous documents by many stakeholder groups, such as 20 mph speed limits.

- There is no discussion of topical problems that make walking difficult and/or dangerous, and which are the subject of campaigns, such as illegal parking on pavements and insufficient time being given at timed pedestrian crossings.

- There is a stated ambition by 2025 "To increase the percentage of children aged 5 to 10 that usually walk to school from 48% in 2013 to 55%". The way in which this ambition was chosen should be transparent. It seems unambitious and it may be that it should be increased.

- There is no proper funding commitment.

- A separate walking delivery plan is needed.

- In conclusion, a major revision of the Plan with regard to walking is required.

Detailed points

Compliance with recommendations on good policy making

Whether the document is called a Delivery Plan, or a Policy, or anything else, it should take account of accepted guidance on good policy making such as that given in the Cabinet Office document Better Policy-Making [3], and in the Civil Service Reform Plan [4].

These documents indicate that the plan should be based on evidence, on a review of international practice, and on lessons learned from previous initiatives, whilst also being open and transparent.

Background evidence

The Plan notes "a steep increase in cycling in London", but there is very little background evidence on walking. This should include the following.

- The decrease in number of walking trips over recent decades

- Casualty rates by mode of travel

Pedestrian fatal and serious injury rates per km are about 20 times those for car occupants [5].

- The high pedestrian death rates compared to the top countries in western Europe

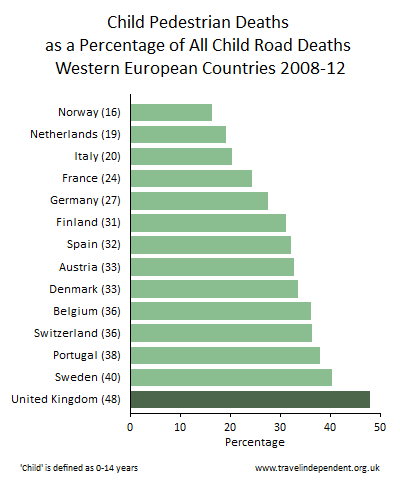

The child pedestrian death rate per million children is about twice as high in the UK as it is in Norway and the Netherlands [6]. This results in an excess of 12 child pedestrian deaths per year compared with Norway and the Netherlands. This relatively poor position for UK pedestrians compared with other western European countries is in contrast to the UK's very good record for car occupants. The result is that

• In the UK, 48% of children killed on the roads were child pedestrians - this is the highest proportion in western European countries.

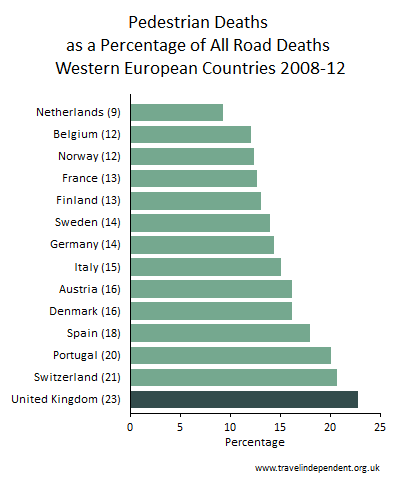

• Including all ages, 23% of UK road deaths were pedestrians - again the highest proportion in western European countries:

|  |

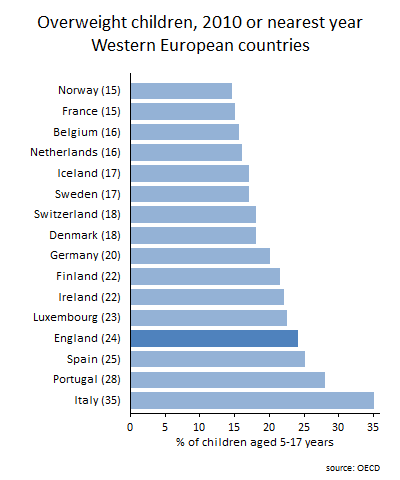

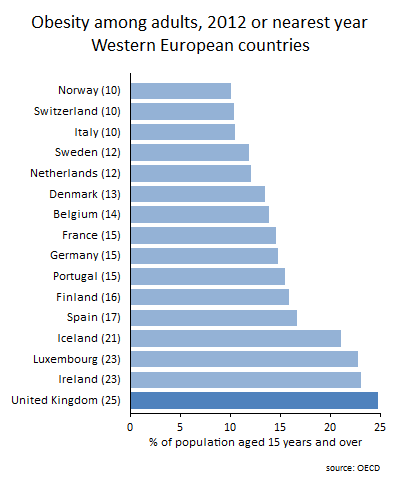

- The high obesity rates in the UK compared to other western European countries

The charts show data from the 2014 OECD report [7].

|  |

Taking these points together gives a picture that the needs of UK pedestrians are being neglected.

The DfT should stop judging road safety purely by total road casualties

The Plan points out (page 9) that "For people to choose to walk or cycle the conditions needs to be right" and that "Concern about safety is also a barrier to people cycling and walking". This demonstrates an acceptance that people are not walking and cycling because of safety concerns. If a neighbourhood is so unpleasant and dangerous that almost nobody walks or cycles, and consequently there are almost no pedestrian or cyclist casualties, this is a public health disaster, rather than a road safety success. And yet numerous DfT documents describe the UK's roads as among the safest in the world purely on the basis of the total road casualties for all modes. This is an overly simplistic approach that should cease.

The National Audit Office made recommendations [8] in 2009 that

The Departments current targets for road safety do not distinguish between different trends in deaths compared to serious injuries, or among particular groups. To increase transparency, the Department should set targets that report separately the numbers of people killed and those seriously injured, and further subdivide these between different groups of road users.

but these recommendations seem to have been ignored. Attention needs to be directed at each mode of transport and casualty numbers should be judged in conjunction with the number of trips not taken due to the perceived road danger. In fact, the ill-health effects of road danger are mainly indirect, from inactivity, rather than direct, from the road casualties.

The gap between the vision and the current facilities for pedestrians

The Plan contains no assessment of the gap between the vision and the current facilities for pedestrians.

The response from councils that no action will be taken at dangerous crossings because nobody has been injured there is a common one. It reflects a severe imbalance between pedestrians and motorised travel in both funding and safety standards. For example, crash barriers are routinely constructed at high risk locations on motorways and other fast roads - not just where people have been injured. There seems to be plenty of funding available for high standards to be met for car occupants, but not for pedestrians.

Many older people have difficulty walking (or running) fast enough to cross dangerous junctions safely. These people do not need the pilot studies in Age-Friendly Cities (mentioned on page 14 of the Plan) "to create physical and social environments conducive to older people walking". In most cases, it is already clear what measures are needed - the urgent need is fair funding via a fair proportion of the roads budget.

The UK's position below other countries in extent of walking provision

The document contains no statement that the UK is behind other countries in walking provision, and needs to catch up.

Many DfT statements refer to the UK leading the world in road safety, but while this may be true for car occupants, it is not true for pedestrians, and this needs to be clearly stated. This will help justify and secure the large funding investment needed.

Past decisions by politicians and officials and the current obesity crisis

The Plan should discuss the relationship between previous decisions by politicians and officials (which have given priority to motor vehicles) and the current obesity crisis.

There is a widespread belief among many stakeholders that previous decisions by politicians and officials are responsible for the current obesity crisis via making car travel safe and easy, and via making walking and cycling unsafe and difficult. This then leads to inactivity, obesity, heart disease, diabetes and cancer. The well-documented fall over several decades in average calory intakes [9] shows that the increase in obesity is not due to people eating more. The Plan should include a consideration of this point, and either accept it or provide evidence to refute it. The DfT seems to be in denial concerning this.

The moral obligation to protect children and other vulnerable pedestrians from the danger created by motor vehicles

Walking is, in isolation, a safe activity. It has been the main means of transport for hundreds of thousands of years. But the introduction of motor vehicles onto streets and roads has made walking dangerous and unpleasant.

Freedom of movement is not only a basic human right, but children by law are compelled to travel daily to school. For many, the only way to travel is on foot. Society has an obligation to children and anyone else wanting to travel by foot to protect them from the dangers created when people travel fast in motor vehicles. This obligation to protect children from motor vehicle danger should be considered as equivalent to the obligation to protect them from parental abuse or from child sexual abuse.

The excess in UK child pedestrian deaths of 12 per year (or one each month) compared to the best countries of Norway and the Netherlands seems to attract no comment in the DfT's annual report - a stark contrast with the attention given to cases of child parental abuse (e.g. Peter Connelly, Victoria Climbié), where the child's name becomes well known. Why is there no determination to look at what is being done in other countries to protect children, and no mention of it in the Delivery Plan?

Potential benefits (including economic benefits) of achieving the vision

The Plan should consider the potential benefits of achieving the vision that was set out, in order to justify the investment of time, energy and funding. Documents that should be considered include Making the Case for Investment in the Walking Environment [10] and The Pedestrian Pound [11].

Previous Dft actions and documents, and any lessons learned

There is no review of previous DfT actions and documents relevant to the vision, and what lessons were learned. The Plan should include such a review or refer to a review or reviews already published.

Why is the vision not already a reality?

There is no consideration in the document of why the vision (which is not new) is not already a reality. There have been many documents advocating a similar vision such as Take Action on Active Travel [12], and Healthy Transport = Healthy Lives [13]. The former document, produced by the Association of Directors of Public Health, collated evidence in favour of a similar vision, put forward detailed recommendations, and showed wide public support by collecting over 100 co-signatory organisations from across society. The Report made a plea:

We call on ministers, civil servants, local authorities and all involved to make a big shift now: invest heavily in walking and cycling, and recreate an environment where children can play in the street and adults lead an active life.

Yet a review in 2012 [14] found that little progress had occurred. This raises some fundamental questions.

- Is it not the role of national and local government to respond to expert recommendations (especially when they have broad public support) and implement them unless there are good reasons for not doing so?

- Is there a systematic failure in the policy-making process in the Department for Transport?

- Do transport ministers travel mainly by car and have little understanding of the problems facing those trying to travel without one?

- Have funding decisions in the past been biased towards the minority of the population who own a car?

- Is there a lack of courage in decision-makers in facing up to possible criticism?

- Should a different decision-making structure be considered?

These questions need to be answered. If they are not, the mistakes of the past will be repeated, and little progress will be made - and some vulnerable children and adults will be seriously harmed - and some will be killed.

Adoption of a Vision Zero / Safe System approach

A Vision Zero / Safe System approach should be adopted, where it is recognised that all road users - pedestrians, cyclists and motor vehicle drivers - will make mistakes from time to time, and provision is made to minimise the consequences of these mistakes. This is absent from the draft Plan.

If we base a child pedestrian safety strategy on an assumption that children will do exactly as they are told 100% of the time, it is inevitable that children will be injured and killed on the roads. Politicians and officials have failed to allow for children not following the strict instructions they are given - instead, they have often put the blame on the children.

The London Assembly document Feet First: Improving Pedestrian Safety in London [15] recommends a Vision Zero approach.

Review of the current Road Safety Strategic Framework

The Plan contains no review of the current Road Safety Strategic Framework [16]. This appears to be failing to have any effect of reducing pedestrian casualties.

Does the available information indicate that the Framework is working as intended, or is no monitoring being done?

Specific measures such as 20 mph speed limits

The document should contain a review of specific measures that have been recommended in numerous documents by many groups, such as 20 mph speed limits, better compliance with existing speed limits, prohibition of parking around schools, presumed liability in the event of collisions, and a lowered legal alcohol limit for drivers. Such a review should include details of how these measures have been introduced in other countries and what lessons were learned.

The British Social Attitude Surveys have consistently shown a large majority of the population in favour of 20mph speed limits in residential streets. For example the 2011 survey [17] found 73% of respondents in favour and 11% against. There is good evidence from the study of London 20mph zones that the slower speeds can roughly halve road casualties [18]. Since 20mph limits are easily affordable within the total roads budget, and there are no technical barriers, the Plan should discuss why 20mph speed limits have not been implemented in the UK in the same way as equivalent limits have been implemented in other countries.

The plan should include measures to tackle poor compliance with speed limits.

Topical problems that make walking difficult and dangerous

The Plan should include a discussion of topical problems that make walking difficult and dangerous, and which are the subject of campaigns, such as illegal parking on pavements and insufficient time being given at timed pedestrian crossings.

Ambition by 2025 to increase to 55% the proportion of children (aged 5 to 10) walking to school

There is a stated ambition (page 5) by 2025 "To increase the percentage of children aged 5 to 10 that usually walk to school from 48% in 2013 to 55%". The way in which this target was chosen should be set out. It seems unambitious and it may be that it should be increased, once the evidence is examined. A target or ambition should be chosen on the basis of evidence from other countries, and from studies of best practice in the UK, and what measures have been successful. Is this how the target of 55% was chosen, or was it merely a round number slightly more than the 2013 figure of 48%?

A proper funding commitment for walking is missing

Transport projects that are viewed as important are given specific funding commitments: HS2, Crossrail, and the building of major roads. Why is a specific commitment to funding walking not given? Is getting children safely to school less important than the projects mentioned?

It is not good enough to say that it is the responsibility of local authorities, without ensuring that they have adequate funds and that they spend them effectively - or to give vague statements about seeking out new funding opportunities as in Annex A of the draft Plan.

The Government has announced an investment of £24bn in the road network in this and the next Parliament [19]. In line with the Public Health recommendations (which had wide public support) [12], 10% of this i.e. £2.4bn should be allocated for pedestrians.

A separate walking delivery plan

There should be a separate walking delivery plan (separate from the cycling delivery plan), or there should be walking sections in a combined Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan. It is not good enough to have a few comments on walking in a document that is principally a cycling delivery plan.

In conclusion, a major revision of the Plan is required

Past decisions by politicians and officials have led to damage to children and other vulnerable pedestrians not just equivalent to, but greater than that resulting from the child sexual abuse that is currently the subject of numerous inquiries.

Children and other vulnerable pedestrians have been badly let down by those in a position of authority, their needs have been largely ignored, and many have been seriously harmed or killed.

The Delivery Plan represents an opportunity for a fresh start with its admirable vision, but the details with regard to pedestrians fall woefully short of what is required, and constitute further neglect of the needs of children.

A major revision is needed.